We use cookies on this site to enhance your experience.

By selecting “Accept” and continuing to use this website, you consent to the use of cookies.

Search for academic programs, residence, tours and events and more.

Aug. 3, 2021

Print | PDFAt a time when the impact of print media is declining, it may be difficult to comprehend how much influence it once held. For the women’s suffrage movement in Britain during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was essential.

“No major organization existed without having an official publication or periodical at the time,” says Maria DiCenzo, professor of English and Film Studies at Wilfrid Laurier University.

Like many other advocacy groups and political movements, suffrage organizations recognized print media’s potential and leveraged it for political purposes. Print media was experiencing a period of expansion and diversification, as it was the chief means of communication in Britain and other industrialized democracies at the time.

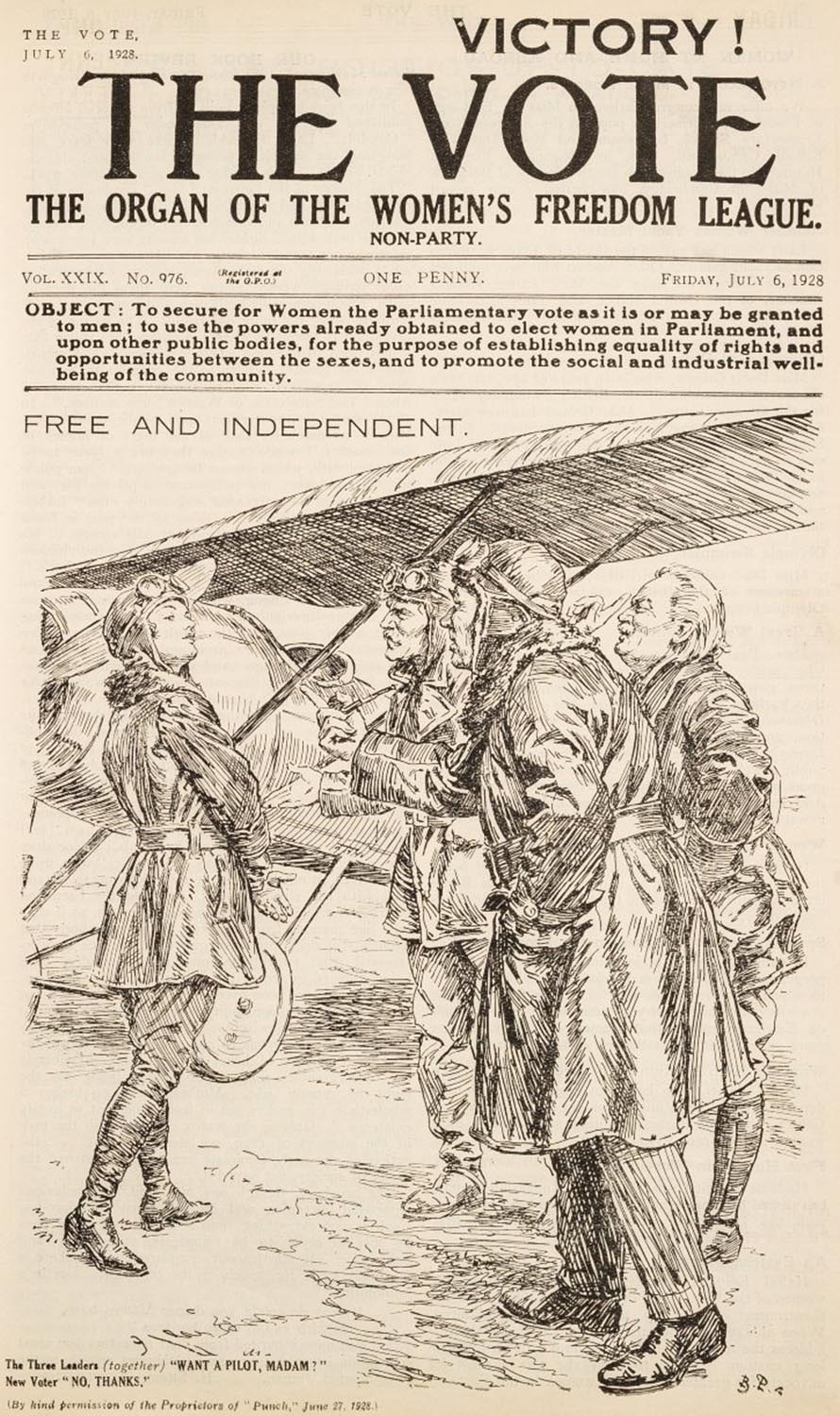

A 1928 issue of The Vote, the official newspaper of the Women's Freedom League.

DiCenzo, who identifies herself as a “feminist media historian,” was introduced to the suffrage periodical press after completing her doctoral research on 20th-century political theatre in Britain. As she began to read periodicals published by feminists across the political spectrum, she realized that they were not just internal newsletters read by a society’s membership but widely consumed and commented upon by the general public.

“I became fascinated by these papers,” says DiCenzo, who has continued to study them for the past 25 years.

The way DiCenzo reads these periodicals is distinct from many other historians, who traditionally use them as sources of information. Rather than the message, it is the medium and the ways in which suffrage periodicals interacted with one another and the mainstream press that has guided her research agenda. By examining the feminist press relationally, DiCenzo has been able to identify the points of unity and disagreement over suffrage within the women’s movement and in British society more broadly.

For the past six years, DiCenzo has turned her attention to the feminist movement in the interwar period, the time between the First World War and Second World War. The British Parliament passed the Representation of the People Act in 1918, which extended voting rights to women over the age of 30 who occupied property. Though some scholars argue that this led to a subsequent decline in feminist agitation, DiCenzo believes it was actually a period of reinvigoration.

Interwar-period conflict within the feminist movement was fought over a wide range of issues related to equality and self-determination, says DiCenzo. By 1925, a heated debate ensued between two of Britain’s most influential feminist periodicals of the 1920s over the meaning of feminism. Conflicting factions known as equalitarians and welfare feminists both hoped to provide women equal access and opportunity in the public sphere but differed in their views of domestic life.

Equalitarians believed that equal opportunity to vote and in the workplace would liberate women from the domestic sphere. On the other hand, DiCenzo says that welfare feminists were trying to “liberate the ‘home’ from the very social norms and meaning that devalued it and made it oppressive” by giving women access to birth control and mothers’ allowances, thereby allowing women self-determination in all aspects of their lives.

Attendees of a debate between suffrage and anti-suffrage societies in Manchester, 1909. (Women's Library, London School of Economics)

These points of contention have been characterized as weaknesses in the feminist movement, but DiCenzo sees them as reflective of the myriad of perspectives of women from different social classes, political backgrounds and religious points of view. Together, they came to define the goals of the political moment, which were most clearly laid out in the feminist periodical press.

Through her research, DiCenzo has concluded that debates over “feminisms” have never been resolved. Regardless, through the efforts of different factions of the movement, progress was made. Together they achieved equal suffrage, helped pass legislation for family allowances and ultimately pushed the feminist agenda forward beyond 1918.

DiCenzo and other feminist scholars have been working for years to incorporate feminist voices into the larger history of the period.

“The biggest loss over the years is how much contained within these periodicals has been ignored, particularly the fact that these women mediated world events from a feminist perspective,” says DiCenzo. “Feminist perspectives on national and world events are treated as somehow separate and not relevant to a broader understanding of those major developments.”

Although DiCenzo retired in June 2021, her work is not yet finished. Her pursuit of feminist voices and their inclusion in the histories of women and 20th-century Britain will continue into retirement. And she will continue looking for them, as she always has, in the feminist periodical press.

This article was adapted from The Bridge, a Laurier Faculty of Arts newsletter written by Eric Story.