We use cookies on this site to enhance your experience.

By selecting “Accept” and continuing to use this website, you consent to the use of cookies.

Search for academic programs, residence, tours and events and more.

Sept. 15, 2022

Print | PDFWhen Norma Jacobs (Cayuga name: Gae Ho Hwako) served as Elder-In-Residence at Wilfrid Laurier University’s Brantford campus, much of her focus was on supporting Indigenous students seeking to reconnect with their Indigenous identities. Students came to her with a need for emotional and spiritual support on their journeys and with questions about their language, culture and clan membership.

In this work, as well as in co-teaching Laurier courses and leading conversation circles with associate professor of Social Work Timothy Leduc, Jacobs found both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students struggled to comprehend the extensive impact of colonial systems on Indigenous families, communities and culture.

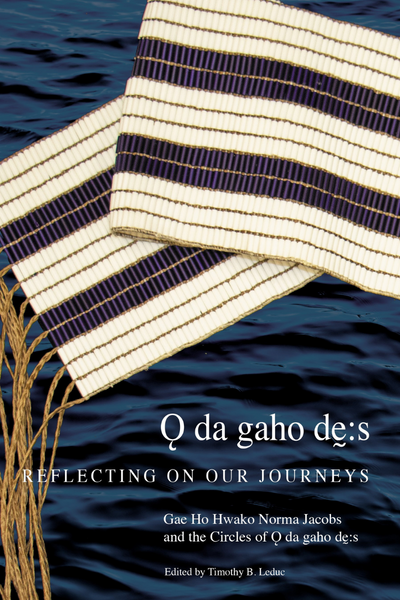

Ǫ da gaho dḛ:s: Reflecting on Our Journeys was born out of these experiences and knowledge. The book, released during the summer and edited by Leduc, contains Haudenosaunee cultural teachings by Jacobs – a knowledge-holder of Haudenosaunee cultural ways, practices and languages – and is structured to mirror a conversation circle.

“It is always about nurturing Ǫ da gaho dḛ:s between us, so that we can communicate with one another and be really clear about who we are in these relationships.”

Following each teaching in the book, four circle participants write their reflections based on their own personal experience with colonialism. The participants come from various backgrounds – some are scholars at Laurier, some writers and some community activists.

Following each teaching in the book, four circle participants write their reflections based on their own personal experience with colonialism. The participants come from various backgrounds – some are scholars at Laurier, some writers and some community activists.

“When we learn something new, we always have to struggle to understand the process and really see how it affects our life,” says Jacobs, who is a Longhouse Faith Keeper and a Cayuga Elder of the Wolf Clan in the Cayuga Nation.

In one section of the book, Laurier PhD candidate and Social Work lecturer Giselle Dias reflects on the prison system’s colonial harms. In another, Lianne Leddy, associate professor of History at Laurier, draws upon her Anishinaabe knowledge and experiences with her daughter to critically challenge the patriarchal assumptions embedded in the English language and Western institutions.

In reading the reflections that came forward in the creation of the book, Jacobs was often brought to tears as the responses would open up perspectives she hadn’t considered.

Storytelling is an integral part of Jacobs’ approach to bringing clarity to these complex topics. With the practice of sharing stories in a circle, participants are able to come to a place of understanding and compassion.

“That whole process of having conversation is understanding one another because we’ve been taught to fear one another as nations and people,” says Jacobs. “We carry each other’s burden, and that way it’s not so heavy and it brings us to that place of equality.”

The understanding of the Two Row Wampum treaty was that neither would interfere with the other and instead travel together as equals. The space between these two lines is Ǫ da gaho dḛ:s.

The concept of the Two Row Wampum features prominently throughout Ǫ da gaho dḛ:s, which can loosely be interpreted as “the sacred meeting space.” In their teachings and conversation circles, Jacobs and Leduc used the Two Row Wampum – one of the first treaties between Indigenous people in North America and Europeans – as a model for how Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples can live and navigate “the river of life.”

The two lines in the Two Row Wampum symbolize a European ship and a Haudenosaunee canoe, each containing the customs, ways and laws of each society. The understanding of the Two Row Wampum treaty was that neither would interfere with the other and instead travel together as equals. The space between these two lines is Ǫ da gaho dḛ:s.

“It is always about nurturing Ǫ da gaho dḛ:s between us, so that we can communicate with one another and be really clear about who we are in these relationships,” Jacobs writes in her introduction to the book.

Colonialism disrupted the spirit of the Two Row Wampum agreement, says Jacobs.

“There’s a lot of work to make sense of how this happened. I don’t think that we could ever reconcile all of those behaviours that were done to our people.”

The first step, according to Jacobs, is to understand who Indigenous peoples are and develop an understanding of their perspectives and world views. This will require what she calls a “restructuring” of Canadian society, including institutions like social work and universities, which were built in the context of colonial systems.

Jacobs encourages everyone to consider the Seventh Generation Principle in the Great Law of the Haudenosaunee: that every decision made today should be considered in the context of its impact on people seven generations into the future. She emphasizes that everyone has a responsibility to be giving, to share and to learn from each other.

On Sept. 1, Jacobs was appointed to a two-year term in Laurier’s Faculty of Social Work as the Elder-in-Residence supporting the journeys of Indigenous PhD students. She says “restructuring” as a form of reconciliation involves continuous and ongoing actions, which she hopes the Laurier community will engage in wholeheartedly.

Members of the Laurier community are invited to attend a hybrid book launch for Ǫ da gaho dḛ:s: Reflecting on Our Journeys taking place Sept. 27 at 2 p.m. Register to attend online or in person at the Brantford Indigenous Student Centre (111 Darling St.) or the Waterloo Indigenous Student Centre (157 Albert St.).