We use cookies on this site to enhance your experience.

By selecting “Accept” and continuing to use this website, you consent to the use of cookies.

Search for academic programs, residence, tours and events and more.

June 8, 2023

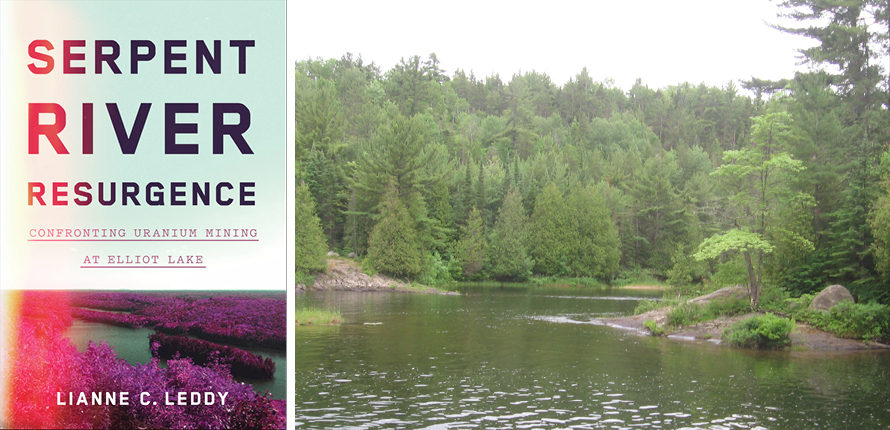

Print | PDFLianne C. Leddy, an associate professor of History at Wilfrid Laurier University, documented a legacy of colonialism and community resistance in her book Serpent River Resurgence: Confronting Uranium Mining at Elliot Lake. In the 1950s, uranium became a valuable commodity as an essential element of the nuclear arms race playing out during the Cold War. Uranium mining began in northern Ontario and the settler town of Elliot Lake emerged.

At nearby Serpent River First Nation, a sulphuric acid plant was built directly on the reserve. A secondary industry in support of uranium mining, it arrived with promises of prosperity for the community. Instead, the short-lived acid plant brought air and water pollution and killed most of the area’s trees. More than half a century later, the social and environmental impacts remain.

Leddy is a member of Serpent River First Nation and first learned of this history at her late grandmother’s kitchen table. Her grandfather, Lawrence, worked at the acid plant and Leddy’s grandmother, Gertrude, later helped mobilize her community to campaign for its cleanup. She is the inspiration for Leddy’s research.

Drawing on extensive archival sources and oral histories, Leddy’s book examines the environmental and political power relationships that continue to affect her homeland. Serpent River Resurgence was recently honoured with three awards from the Canadian Historical Association: the Best Scholarly Book in Canadian History Prize, the Indigenous History Book Prize and the Clio Prize for Ontario.

"This is a must-read for any person wanting to engage in reconciliation and to understand that First Nations people have been on the frontlines of resource development and have suffered the consequences,” says Chief Brent (Nodini’inini) Bissaillion of Serpent River First Nation. “We must be reminded of our past relationships and how we got to this point, and we need to hear the truth.”

During Indigenous History Month, we asked Leddy about her memories of childhood in Elliot Lake, learning from her Elders and the impact she hopes to have through her research.

Elliot Lake is a settler town that only exists because of the Cold War uranium boom. The majority of school kids had a parent who worked at one of the mines or in a job that was directly related to mining, including my father. While the environmental impacts were far from hidden, I don’t remember that part of the story being emphasized in town, at least not until the last mine closed in the mid-1990s.

For the most part, I learned about the environmental impacts of both the mines and the acid plant from my grandmother and other community leaders who lobbied for the cleanup of the acid plant site and drew attention to the importance of the watershed.

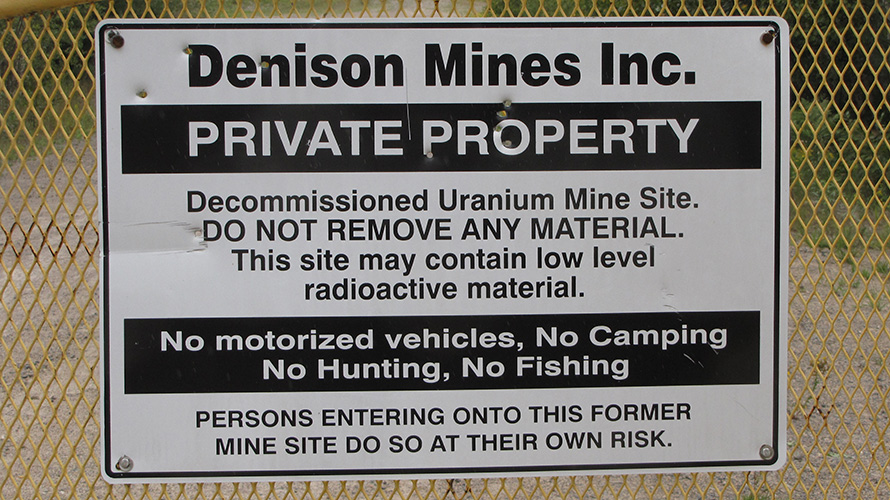

Caution sign at a tailings management site near Elliot Lake.

It closed in the 1960s, but the buildings and materials were simply abandoned. The military blew it up in the summer of 1969, leaving debris everywhere, but that was obviously not an effective way to decommission the site. The community had to mobilize to have it cleaned up properly, which didn’t happen until the late 1980s.

The watershed will always have to undergo monitoring and the community likely won’t be able to fully use the land where the acid plant was. Serpent River is tied to our traditions and history, and it became unsafe for families who relied on it for drinking water, hunting and fishing. My grandmother told me about taking her children to swim in the Serpent River because it was clearer than the bay where the acid plant was located. Then she discovered that there was radium-226 in the river and, in fact, it had not been as safe as she thought.

It was a gift to be able to learn from my Elders in this way. It was moving to hear them talk about their advocacy and share their stories, as frustrating or empowering as they were. I will always be grateful for their generosity and patience in explaining these important events. Remembering their experiences drove me when I encountered my own training and career challenges, so I guess you could say I learned a lot as both a researcher and an Anishinaabekwe. Their stories deepened my understanding of our homeland and our responsibilities to it.

"I wanted to remind Canadians that settler colonialism disrupted Indigenous lives throughout the 20th century and continues to do so today."

When I was in grad school, much of the historical literature focused on different time periods of colonization in what is now Canada, such as the fur trade and western settlement. In my own family history, I was seeing a form of colonialism that had familiar patterns and yet was totally new and very much tied to the geopolitics of the Cold War. I wanted to remind Canadians that settler colonialism disrupted Indigenous lives throughout the 20th century and continues to do so today. I’m seeing these same stories play out in a different century, be it uranium mining or the extraction of other minerals that are now seen as critical to Canada’s geopolitical and economic potential.

I also wanted to focus on resistance, always thinking about how I could honour the stories of my Elders. Their experiences demonstrate how our leaders have asserted their authority against capitalistic extraction and environmental racism for a very long time, even within the confines of the Indian Act and the reserve system.

My research provides a clear example of what can go wrong – and how long-lasting the impacts can be – when Indigenous rights are compromised by larger governmental and private extractive forces. I heard my Elders say that they weren’t aware of the potential impacts when they were faced with these choices in the 1950s. If Canada is serious about adopting the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, then it must also be committed to ensuring Indigenous communities and nations have free, prior and informed consent for any projects on our home territories.